Despite Deferment Of The Care Act Part 2, Councils Still Face Significant Market Sustainability Challenges

Underlying sustainability of the social care market for older people remains the key issue facing the long term care sector, and is the cornerstone of newly published analysis conducted by healthcare expert LaingBuisson – with support from the County Councils Network (CCN).

The social care funding crisis has for a long time been widely debated. However, through ground-breaking profitability analysis and the innovative use of market dynamics modelling, a recently completed LaingBuisson /CCN project has provided the necessary ingredients to predict the severe consequences for sustainability of the care home sector for older people, based on current, and accelerating, adverse market trends.

Having presented the findings of the (separate) CCN Summary Report to the Department of Health, ADASS (Association of Directors of Adult Social Services) and council leaders through a series of meetings led by CCN, it is now hoped that this robust evidence base will pave the way for a fuller debate between all interested parties on how to address the sustainability issues facing the sector, as well as how best to revise the proposed Care Act Part 2 provisions, now deferred for implementation until 2020.

While the results do not take account of the introduction of the living wage (announced after completion of the study), raised publicly with the Chancellor today in a letter co-signed by five of the country’s largest providers, it is recognised that this will have a further marked adverse impact on sustainability, which can readily be incorporated in the models.

LaingBuisson’s County Care Markets – Care Market Sustainability & The Care Act* presents key overall findings from evaluation of the main financial implications of the Act for local authorities, providers of residential care and nursing homes, older people needing care, and for sustainability of the market.

This overall report is based on results of work undertaken in analysing the care home markets and Care Act implications in depth for 12 sample county councils and unitary authorities, considered to be representative of county and unitary councils across England.

Analysis presented in this report is divided into two distinct but inter-related parts:

Underlying sustainability

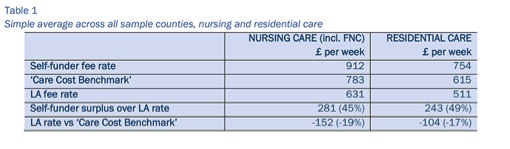

First, the existing, underlying care home market has been assessed, in terms of levels of fees, existence, levels and implications of cross-subsidies (see Table 1, below), profitability, levels of care home capacity, issues and risks relating to sustainability, based on comprehensive studies in the sample councils (anonymised in the report). Alongside full access to LaingBuisson’s long established database of older people’s care services, trends have been explored, changes in demand estimated and the implications of all the key issues and trends explored in dynamic market models which reflect the inter-relationships between demand, supply, prices, returns, closures, new build and other key variables.

The average fee analysis in Table 1 provides firm evidence for the first time, to confirm that the viability of the care home market has only been sustained over many years, and even more so recently, by the premiums which those paying for their own care (self-funders) pay, to make up the shortfall in the level of local authority fees typically paid, compared to the full cost of care. The cost of care has been estimated as a ‘care cost benchmark’, utilising LaingBuisson’s extensive surveys, costing databases and methodologies, with costs tailored specifically to the levels of costs incurred by providers in each local council area.

While this new analysis reveals that the cross-subsidies required from self-funder residents in the same care home vary significantly around the country, it more importantly shows that care home financial viability and market sustainability risks vary enormously. These findings are based on the extent of the council fees shortfall, the surplus self-funders are paying and the relative proportions of council-funded and self-funder residents within care homes.

Given the increasing under-funding and pressure on council fees over the last five years, sustainability risks are already typically very high in the ‘less affluent’ areas of the country, where council and self-funder fees are lowest relative to costs, the proportion of council-funded residents is high, and numbers of self-funders are low.

With steadily increasing demand (due to demographic changes), severe shortages of nurses and other care staff and the need to pay more to attract them, as well as the likelihood that local authorities will find it increasingly difficult to increase their fees to match the expected staff cost increases, LaingBuisson’s dynamic models have been used to predict reductions in provider profitability, increasing home closures and insufficient investment in the provision of new capacity being built, resulting in increasing shortages in care home capacity, accelerating over the next ten years.

The high additional risk of increasing ‘polarisation’ in the market has also been explored, with increasing evidence that many providers are focusing more on supporting self-funders, to the exclusion of those paid for by the councils, leading to less scope for cross-subsidies to shore up the market, fewer places for councils and increasing unaffordability of fees to the councils.

The models have then been used to explore the impact of various fee, cost and policy scenarios. For example, it might be possible for some councils to implement additional policies to increase community support, to enable even more older people to stay in their own existing homes for longer, or to move instead into extra care housing, thereby diverting a further proportion of the increasing demographic demand for residential or nursing care home places, and reducing occupancy pressure on limited care home capacity. The impact of so doing, if this is considered practicable, is illustrated in Figure 1 (below).

From the actual results for this sample council, it can be seen that to reduce use of nursing home demand by a further 1% of an expected increase in demand of 3% per annum would be likely to result in changing a likelihood that capacity available would not be able to stay ahead of demand, to one in which demand is reduced, capacity is not required to expand as far and a modest though still necessary surplus of capacity over demand is achieved (bearing in mind that it is unrealistic for care homes to operate at in excess of 95% occupancy). It should be stressed, however, that this result is by no means achievable for all councils modelled.

Councils can test out the likely impact of implementing such policies, through varying the model assumptions. However, in practice it should also be recognised that this will be likely to be more difficult in nursing care than in residential care, and that there are now real limits to how many more older people can be supported to stay at home, as a proportion of those needing significant levels of care, given that those older people now going into care are already mainly those who are very old (often over 85) and physically, as well as possibly mentally, very frail.

Scenarios can also be used to demonstrate that if the fundamental root cause of the crisis is addressed, by increasing funding, so that council fees can be raised to meet the full costs of care, then this should go a long way towards addressing shortages in the market and improving sustainability.

Care Act implications and impact

The implications of the Act have been overlaid on changing market conditions to examine the additional, potential adverse impact and risks arising from key provisions. This work focused, in particular, on:

- The implications of what has become referred to as ‘market equalisation’, resulting from the possible erosion of the differential between the high fees self-funders pay for care and the insufficiently low fees councils are paying for equivalent care i.e. erosion of the significant cross-subsidies which exist in the care home market (through councils arranging care for self-funders at their low ‘usual cost of care’, as well as other downward fee pressures due to the high ‘like-for-like’ self-funder premiums being publicised for the first time, in care accounts and elsewhere)

- The extra financial burden on councils of supporting those falling within the higher £118,000 assets threshold

- The complication and opportunity afforded for providers by the system of ‘top-ups’, and particularly the implications for fee levels and care home sustainability of own resource ‘top-ups’, which might afford some financial relief, in respect of the increasing numbers of residents being funded by councils at lower fees, under the higher assets threshold

- The likelihood or otherwise of financial benefits actually accruing over time, in practice, to those receiving care, if the cumulative cost of their care, at the council ‘usual care costs’ for support, eventually exceed the care cap, of £72,000; the iniquities in how the extent of benefits receivable will vary around the country are explored, as well as the broad impact for councils

- Likely behaviours and responses of self-funders to these changes, constraints and opportunities are explored

- Possible responses from providers to all these changes and constraints are explored, including factors affecting the extent to which they would be able to resist pressure to reduce self-funder fees, and the possibilities for further service differentiation and polarisation, and their impact

Implications of all these changes have again been explored in the dynamic market models, in terms of their potential impact on further threatening provider sustainability and exacerbating capacity shortages. This analysis also brings in LaingBuisson’s unique Wealth Model to consider the implications of the (now delayed) extension to the asset threshold, on gross and net funding requirements for councils, super-imposing the results on the underlying market realities, risks and trends.

It is believed that the results of this evaluation have been influential in the recent decision by the Department of Health to delay the roll out of the key Care Act Part 2 provisions until 2020. While this is understandably upsetting for less well-off older people hoping to obtain some greater financial contribution to and cap on the cost of their care soon, it will provide a much needed opportunity to address the key issues and challenges which are being, and will be, faced by councils up and down the country.

Commenting on the report, LaingBuisson’s lead consultant on the project, David Roe said:

‘Councils still have a new responsibility now, under the Care Act Part 1, for ensuring the sustainability of good quality provision of care services in their local markets. This poses a major challenge for them, especially with funding for social care under such pressure, as it is not easy to be knowledgeable about the market for self-funders with which the fortunes of council placements are so inextricably linked.’

This report is the first level entry point of the new CareSustain consultancy service now being launched by LaingBuisson, building directly on this work already completed for the consortium of 12 councils, using the comprehensive care home database, analysis tools and dynamic market models.

CareSustain will provide a means by which local authorities can deliver this new responsibility for ‘market shaping’ and ‘market management’ of their local care markets, through comprehensive analysis of existing services and increasing numbers of older people likely to be needing care home support, and projections made based upon a series of funding scenarios. Researchers and consultants will work ‘hands on’ with councils and commissioners and, through the use of the dynamic market models, will present comprehensive data on the fundamental economic workings of their markets, along with the impact of a range of changes, including funding, population change, market investment (and shrinkage) and political will.